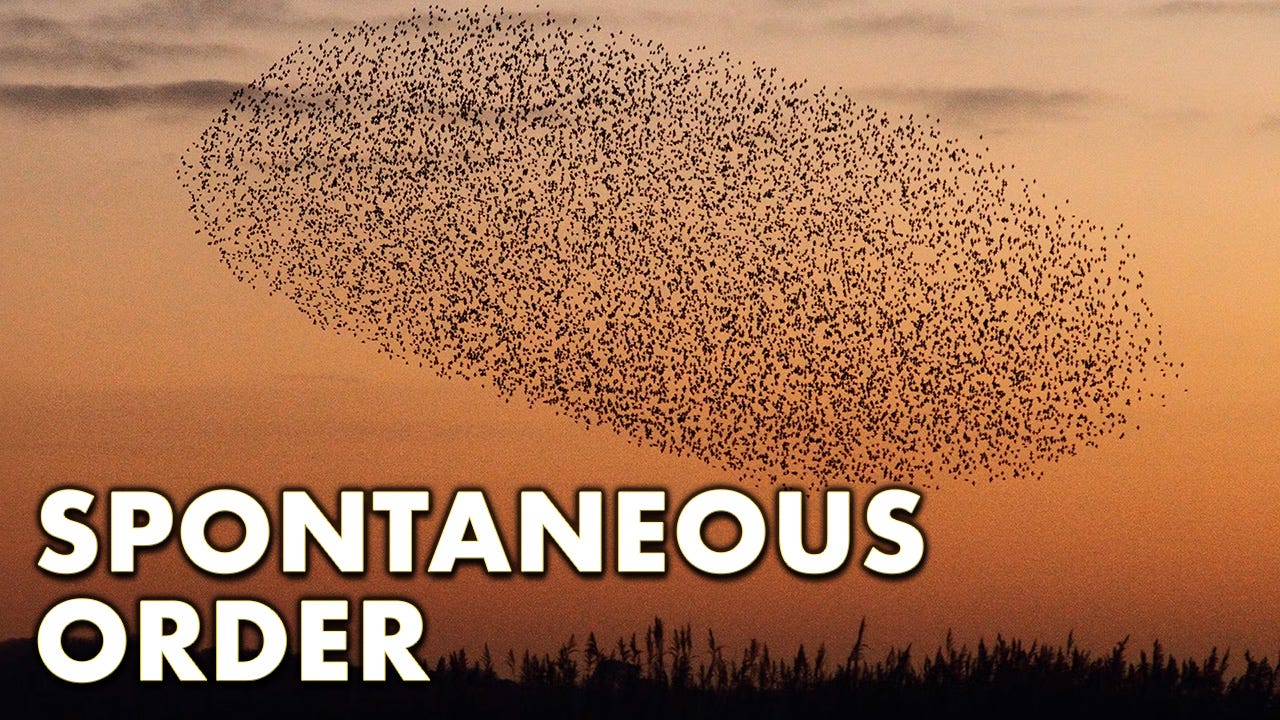

A Brief Introduction to Spontaneous Order

by James Corbett

corbettreport.com

September 21, 2025

Unless you were lucky enough to get one of the signed, hardcover collector edition copies that was offered for Corbett Report members only earlier this year, up until now REPORTAGE: Essays on the New World Order was only available in paperback. But I'm pleased to announce that has changed!

You can now order a hardcover edition of REPORTAGE from wherever fine books are sold (until they're not). You can find purchasing options on the REPORTAGE website, you can find it at any major bookseller online, or you can ask any bookstore in the world to order it for you by ISBN number.

For the record, the ISBN numbers for both the paperback (ISBN-13: 9798991655200) and the hardcover (ISBN-13: 9798991655248) editions are on the bottom of the REPORTAGE website.

In honour of this momentous occasion, I present to you one of the essays from that 20-essay volume, "A Brief Introduction to Spontaneous Order." Enjoy!

(And for all those asking for an audiobook edition of the book, all I can say is . . . stay tuned!!!)

“A Brief Introduction to Spontaneous Order”

from REPORTAGE: Essays on the New World Order

Quick. What do you think of when you hear the word “order”?

If you’re like most people, the first thing that comes to mind is “law and order”—the old adage connoting justice and safety in a well-regulated society. That’s no surprise. After all, the pressing need to restore “law and order” is invoked by any number of politicians in any number of countries around the world every single day. And, if nothing else, that phrase has been drilled into the minds of the television viewing public since the launch of the legal drama series Law & Order in 1990.

Politically savvy folks—this book’s readers among them, no doubt—will likely think of “New World Order,” a phrase popularized by President George H. W. Bush in his now-infamous September 11th (1990) speech.[1] Known by its acronym, NWO, the New World Order actually boasts a colourful past that dates back to the post-WWI era of Wilsonian diplomacy[2] and to H. G. Wells’ 1940 book of the same name.[3]

Researchers of the esoteric may even connect the word “order” to the Latin Ordo Ab Chao, or “order from chaos,” which is, not coincidentally, a motto of the 33rd Degree of the Scottish Rite of Freemasonry.[4] Also not coincidentally, “order out of chaos” perfectly describes false flag terrorism and other methods of manipulating public opinion carried out by a handful of influential individuals who are in a position to wreak havoc for the purpose of imposing their pre-ordained “order.”

But whether we’re discussing “law and order” or the “New World Order” or “order out of chaos,” we’re ultimately talking about the same thing: an “order” based on a hierarchical view of society, in which the lawmakers and their corporate cronies seek to regulate, proscribe, manipulate, inhibit, and control the actions of the masses.

So, what if I were to tell you that there’s an entirely different concept of societal order—one that not only rejects hierarchical “order” but actually refutes the concept of top-down control? Well, there is, and it’s called “spontaneous order.”

The hierarchical model of control orders society in a pyramidal structure where rules and regulations dictated by the “elite” at the top are forced on the masses at the bottom by a bureaucratic class in the middle. Spontaneous order, on the other hand, posits that society best functions as a decentralized network of free individuals participating in voluntary interactions.

The principle of spontaneous order has arguably been around since the 4th century BC, when Chinese philosopher Zhuang Zhou conceived the idea that “Good order results spontaneously when things are let alone.”[5] It was further developed in the 18th century by Scottish Enlightenment intellectuals[6] and in the 19th century by thinkers like Frédéric Bastiat.[7] Not until the 20th century, however, was the theory of spontaneous order named, codified, and popularized by Austrian-born philosopher and economist F. A. Hayek.

In his 1966 article on “The Principles of a Liberal Social Order,” Hayek described spontaneous order this way:

The central concept of liberalism is that under the enforcement of universal rules of just conduct, protecting a recognizable private domain of the individuals, a spontaneous order of human activities of much greater complexity will form itself than could ever be produced by deliberate arrangement.[8]

When put into ordinary English, Hayek’s observation is at once embarrassingly simple and surprisingly profound: the social order that arises from the free choice of individuals acting to protect their own interests will always be more secure and more complex than any rationally ordered, centrally controlled system could ever be.

To see why this is so, let’s turn to Leonard Read’s ingenious 1958 essay, “I, Pencil,” in which an ordinary pencil narrates the unexpectedly complex process by which it is assembled and manufactured from its constituent ingredients:

I, Pencil, simple though I appear to be, merit your wonder and awe, a claim I shall attempt to prove. In fact, if you can understand me—no, that’s too much to ask of anyone—if you can become aware of the miraculousness which I symbolize, you can help save the freedom mankind is so unhappily losing. I have a profound lesson to teach. And I can teach this lesson better than can an automobile or an airplane or a mechanical dishwasher because—well, because I am seemingly so simple.[9]

The central idea of the essay is that, as simple as the pencil appears to be, “not a single person on the face of this earth knows how to make me.”

Why not? Because the creation of a pencil is not a one- or two-step process of assembling a few locally obtained materials in a factory, but a globe-spanning operation involving the harvesting of cedar in Oregon, the mining of graphite in Ceylon, the collection of clay from Mississippi, the reaping of rapeseed in Indonesia, and the gathering of dozens of other natural resources from similarly far-flung locations.

Then, each of these products has to be prepared in its own way. The cedar logs are shipped hundreds of miles from their forest of origin to be cut, kiln-dried, tinted, waxed, and kiln-dried again. The clay is refined with ammonium hydroxide, mixed with graphite and sulfonated tallow, and baked at 1,000 degrees Celsius before being treated with a hot substance comprised of candelilla wax from Mexico, paraffin wax, and hydrogenated natural fats. The oil from the rapeseed is reacted with sulfur chloride and mixed with various binding, vulcanizing, and accelerating agents.

As confusing as this pencil recipe is threatening to become, it is but a partial list of constituents, and it only scratches the surface of what is really involved in coordinating the assembly of these ingredients. Just think of all the people involved in the mining and transportation of the graphite for the pencil’s core. They include not only the miners of the graphite in Ceylon, but also those who make their mining tools . . . and those who make the paper sacks the graphite is transported in . . . and those who make the string for tying the paper sacks . . . and those who load the sacks onto ships for transport . . . and those who make the ships themselves.

Then there are the ship’s captain and crew, the harbour masters and lighthouse keepers who guide the ships to their destination, the truck drivers and train conductors and airplane pilots who transport the materials the rest of the way to the factory, not to mention the employees in the service industries supplying all these workers with food and clothes and other necessities. And that’s just the graphite.

In the end, it’s truly mind-boggling to contemplate the complexity of the pencil’s production. Surely no one person could itemize and keep track of all this activity, let alone direct it all. And yet it goes off without a hitch, creating millions of new pencils each year to be used by people in every walk of life in every corner of the globe. The “simple” little pencil sitting on your desk is proof of that.

The lesson of Read’s essay is that, counterintuitive as it may seem, extremely complex operations require no organizing body to order them. In fact, given the limits of our knowledge, no such body could even exist. What does exist, as evidenced by these complex operations, is spontaneous order.

Intriguing as Read’s insight into complexity is, it may still be unclear how far this insight can be extended beyond the production of pencils. So, let’s look at a different example of something we use every day: automobiles.

Statistics show that driving a car is one of the most dangerous activities we undertake each day.[10] To many of us—steeped as we are in the mindset of top-down control through laws and regulations—the idea of removing traffic lights, speed limits, lane markings, and other devices for demarcating the “rules of the road” sounds insane. Surely the rules of the road are what keep traffic flowing smoothly, aren’t they? Surely the withdrawal of these injunctions would lead to a rise in accidents, wouldn’t it?

Would you believe that just the opposite is the case? It’s true. Every time traffic restrictions have been removed in towns and cities across the world, the result has been safer streets—not to mention the added perks of reduced commute times and more courteous, less-stressed drivers and pedestrians.

If you’re incredulous at this claim, consider what happened in the English town of Portishead, whose experiment in removing traffic lights from a key junction was so successful that the townsfolk decided to make it permanent.[11] Far from a fluke, Portishead is just one data point in a growing body of evidence that the road design ideology known as “Shared Space” actually works to the benefit of all.[12]

Relying on the principles of spontaneous order, Shared Space advocates postulate that making the road “riskier” in fact makes them safer. Rather than forcing drivers to negotiate with the impersonal and inflexible rules of the road (signs, lights, and markings), roads without such regulations require them to negotiate with the other drivers directly. Thus, instead of seeing other road users as mere obstacles between themselves and the next green light, drivers are now compelled to see and interact with their fellow road users as actual humans.

Hans Monderman, a Dutch traffic designer who was one of the pioneers of this approach to rethinking the roads, developed over 100 Shared Space plans in the provinces of Friesland, Groningen, and Drenthe. He observed of the current system, in which wide roads are plastered with plenty of signs presuming to regulate and manage every action that the driver takes: “All those signs are saying to cars, 'this is your space, and we have organized your behavior so that as long as you behave this way, nothing can happen to you.’ That is the wrong story.”

Monderman also believed the existing system degrades and dehumanizes drivers and at the same time deceives them into a false sense of security. “When you treat people like idiots, they’ll behave like idiots,” he reasoned.[13] And vice versa: when we treat adults as capable, independent human beings, they will, more often than not, rise to the challenge and act accordingly.

Shared Space is no mere pipe dream; it has already been implemented in numerous towns across Europe, from Ipswich in England to Ejby in Denmark to Ostende in Belgium and Makkinga in the Netherlands.[14] The result has been a dramatic decline in accidents across the board even as commute times have been significantly reduced. It seems that drivers, when left to negotiate with others for space on unrestricted roads, do act like the adults they are, and a type of order emerges from their civility.

But can spontaneous order govern us in other settings, even ones where criminality is the norm? After all, it’s one thing to bring about spontaneous order on the roads, but quite another to implement it in institutions designed to catch, convict, sentence, and lock up robbers, rapists, and murderers. Is it possible, then, to deal with felons differently from the way our current system does? Can we replace legislators and law enforcers, attorneys and judges, prison wardens and guards with a decentralized, non-hierarchical, non-authoritarian system of justice? What would such a system look like and how would it operate?

Here again, the notion of giving free rein to spontaneous order may seem absurd, but only because we’ve been conditioned to believe that the current setup of legislatures, courts, police departments, and penitentiaries is the sole form of justice that is effective. Under the established system, we have decided that “law” is whatever is voted into existence by legislators, gaveled down by judges, or attested to by police. We have also decided that ordering offenders to pay fines to the state or locking them in cages for prescribed periods of time or compelling them to work “community service” hours are the only possible ways to exact justice for their crimes.

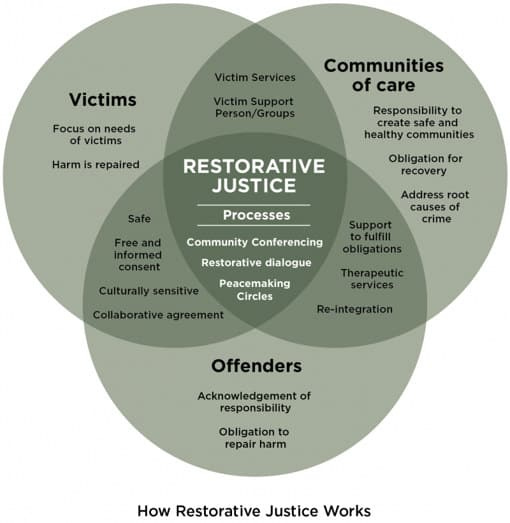

Flying in the face of our customary system of retributive justice, however, is an altogether different conception of jurisprudence—one built on what is called “restorative justice.” In restorative justice, victims and members of the community are invited to come together and decide how they want to deal with the criminal who has harmed them individually and has thus harmed society.

As opposed to the restrictive system of retributive justice, in which the end point of any successful prosecution is a proscribed fine or prison sentence, the restorative justice model opens the possibility for a wide range of outcomes. What if, say, the victims of a robbery, in tandem with a jury of peers selected from the community, decide that everyone would benefit more from confronting and dialoguing with the offender than they would from locking him up in a prison cell for “X” number of years? In other words, why not give victims of crimes a say in what happens to their transgressors?

Just as with our previous examples, letting spontaneous order operate in the penal system might seem counterintuitive. Yet the restorative justice process has been shown to leave victims with less post-traumatic stress and less longing for revenge than does retributive justice. What’s more, the restorative method renders violent offenders less likely to re-offend than those who undergo traditional court trials.[15] The process has been used to great effect literally all over the world, from the dangerous slums of urban Brazil[16] to Hawaiian prisoner rehabilitation programs[17] to a growing number of schools.[18]

We’ve touched on ways the economic system, the road system, and the justice system can benefit from spontaneous order. In each case, we’ve proved that central planners and glorified “lawgivers” are not needed to maintain “order.”

This is not to say that we can transition from a highly centralized society to a completely decentralized one overnight. We have been programmed our whole lives to interact with others through the laws, rules, and procedures constructed by our top-down, federalized system of government. It will take much deprogramming for us to discover how to negotiate with our fellow human beings without such institutions of top-down control. But it can be done.

In effect, we are on the cusp of a transition from dependence—dependence on “Mommy” government to wipe our bottoms and “Daddy” government to mete out punishment and “Big Brother” government to watch our every interaction—to independence as we learn how to order and govern ourselves. Completing the transition will not be easy, nor will the final outcome be utopian; there will always be lawbreakers and those who reject the social order. But we must understand that the false belief that disorderly elements can be dealt with only by ceding more of our power to centralized authorities is exactly what has led us to the brink of economic and societal collapse.

History is replete with great thinkers who have gestured toward this simple truth: “That government is best which governs least.” You may recognize this phrase by Henry David Thoreau,[19] but do you know the context in which he wrote it?

I heartily accept the motto, ‘That government is best which governs least’; and I should like to see it acted up to more rapidly and systematically. Carried out, it finally amounts to this, which also I believe—‘That government is best which governs not at all’; and when men are prepared for it, that will be the kind of government which they will have.[20]

There, in a nutshell, is our lesson on spontaneous order. As our civilization has matured, we have been gradually learning how to govern ourselves. Someday, when we have outgrown our adolescence, we will no longer need the ineffective “order” promised by governments and would-be rulers.

This concept of spontaneous order and self-governance, radical as it may appear to our 21st-century selves, is timeless wisdom that has been passed down through the generations for thousands of years. Chinese philosopher Lao Tzu put it this way in Chapter 57 of the Tao Te Ching more than two millennia ago:

Do not control the people with laws,

Nor violence nor espionage,

But conquer them with inaction.

For:

The more morals and taboos there are,

The more cruelty afflicts people;

The more guns and knives there are,

The more factions divide people;

The more arts and skills there are,

The more change obsoletes people;

The more laws and taxes there are,

The more theft corrupts people.

Yet take no action, and the people nurture each other;

Make no laws, and the people deal fairly with each other;

Own no interest, and the people cooperate with each other;

Express no desire, and the people harmonize with each other.[21]

END NOTES

Bush, George H. W. “Address Before a Joint Session of the Congress on the Persian Gulf Crisis and the Federal Budget Deficit.” George H.W. Bush Presidential Library & Museum. archive.is/nR8DF ↑

Conway-Lanz, Sarh. “World War I: A New World Order—Woodrow Wilson’s First Draft of the League of Nations Covenant.” Library of Congress. April 5, 2017. archive.fo/plzEp ↑

Wells, H. G. The New World Order. (London: Secker and Warburg, 1940). ↑

“Ordo Ab Chao.” The Masonic Dictionary Project. archive.fo/P3DXH ↑

Rothbard, Murray N. “The Ancient Chinese Libertarian Tradition.” Mises Institute. archive.fo/EYjb0 ↑

Barry, Norman. “The Tradition of Spontaneous Order: A Bibliographical Essay by Norman Barry.” Online Library of Liberty. archive.fo/w2svl ↑

Bastiat, Frédéric. “Natural and Artificial Social Order.” The Library of Economics and Liberty. archive.fo/4IlVT ↑

Hayek, F. A. “The Principles of a Liberal Social Order.” Il Politico, vol. 31, no. 4. 1966. Page 603. ↑

Read, Leonard E. “I, Pencil: My Family Tree as told to Leonard E. Read.” The Library of Economics and Liberty. archive.fo/IkG4X ↑

McMillin, Zach. “The most dangerous activity: driving.” The Seattle Times. January 5, 2010. archive.fo/HvsJk ↑

McKone, Jonna. “‘Naked Streets’ Without Traffic Lights Improve Flow and Safety.” TheCityFix. October 18, 2010. archive.is/7PUoS ↑

Toth, Gary. “Where the Sidewalk Doesn't End: What Shared Space has to Share.” Smart Growth Online. October 26, 2016. archive.fo/6B1CK ↑

“Hans Monderman.” Project for Public Spaces. December 31, 2008. archive.fo/x15Aw ↑

Schulz, Matthias. “Controlled Chaos: European Cities Do Away with Traffic Signs.” Spiegel Online International. November 16, 2006. archive.fo/nMyDD ↑

Wachtel, Joshua. “Restorative Justice: The Evidence — Report Draws Attention to RJ in the UK.” International Institute for Restorative Practices. May 16, 2007. archive.fo/IiEBu ↑

Wachtel, Joshua. “Toward Peace and Justice in Brazil: Dominic Barter and Restorative Circles.” International Institute for Restorative Practices. March 20, 2009. archive.fo/gwtey ↑

Walker, Lorenn and Rebecca Greening. “Huikahi Restorative Circles: A Public Health Approach for Reentry Planning.” Federal Probation Journal, vol. 74, no. 1. June 2010. archive.fo/o5cKS ↑

Moss, Vanessa. “Healthier Delray Beach helps bring Restorative Justice Practices to a local school.” Palm Health Foundation. October 30, 2017. archive.fo/IuPMf ↑

Volokh, Eugene. “Who Said ‘The Best Government Is That Which Governs Least’?” Foundation for Economic Education. September 16, 2017. archive.fo/8eSv8 ↑

Thoreau, Henry David. “On the Duty of Civil Disobedience.” Project Gutenberg Australia. archive.fo/Usjji ↑

Tzu, Lao. Tao Te Ching. “Chapter 57. Conquer with Inaction.” Zenguide. archive.fo/AmYlL ↑

Like this type of essay? Then you’ll love The Corbett Report Subscriber newsletter, which contains my weekly editorial as well as recommended reading, viewing and listening. If you’re a Corbett Report member, you can sign in to corbettreport.com and read the newsletter today.

Not a member yet? Sign up today to access the newsletter and support this work.

Are you already a member and don’t know how to sign in to the website? Contact me HERE and I’ll be happy to help you get logged in!