by James Corbett

corbettreport.com

October 13, 2024

Have you ever asked someone to make you a sandwich?

What?? You have??!

You heartless monster! Do you have any idea how unbelievably difficult it is to make a sandwich? Do you have the slightest clue how much backbreaking labour goes into the construction of that bready concoction? Do you understand how incredibly expensive it is to assemble that portable meal?

No? Well, you're about to! Sit back and marvel at the story of a man who actually made a sandwich!

And if making a sandwich sounds utterly mundane to you, then I feel sorry for you. You obviously fail to appreciate the absolute miracle of human community that is taking place around us each and every day—a miracle that makes everything of value in our lives possible.

Prepare yourself for the most important lesson you will ever learn: how to make a sandwich.

A Man Makes A Sandwich

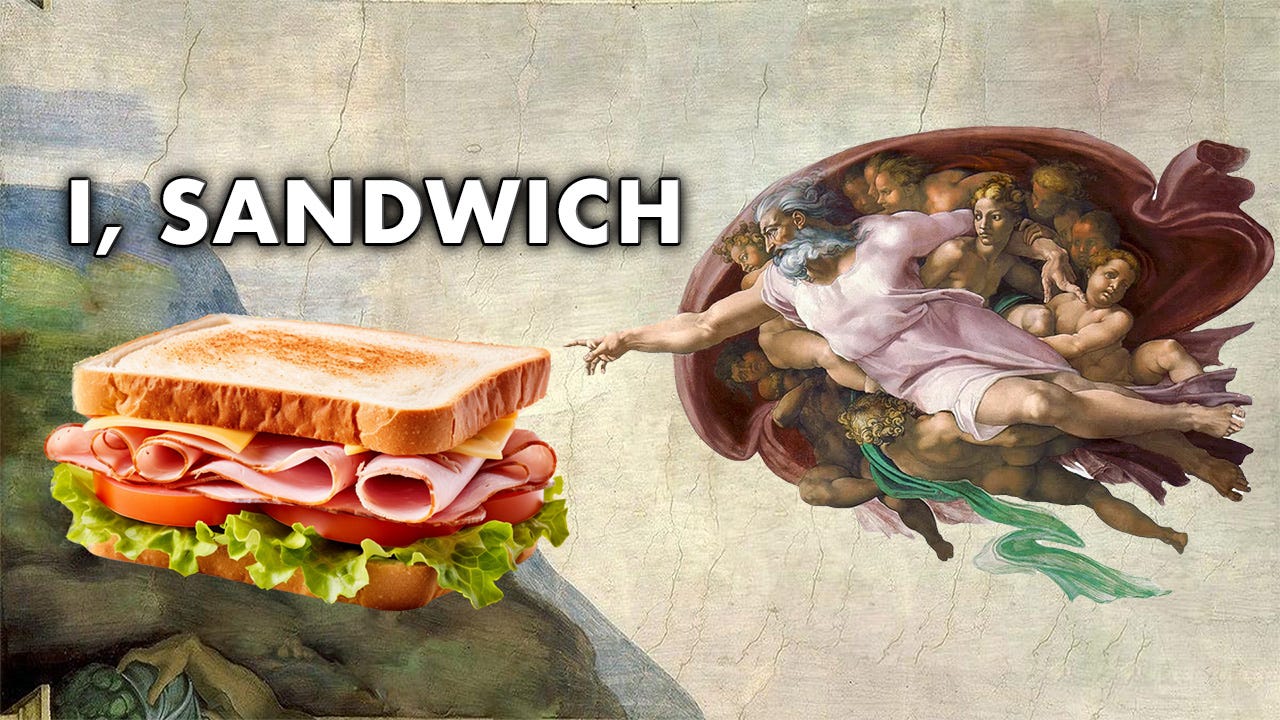

In 2015, Andy George set out to make a chicken sandwich. Amazingly, it took him only $1,500 and six months to complete his task!

Confused? Well, you see, he didn't make a sandwich at home from store-bought ingredients. Instead, he set out to actually make the sandwich (and all of its ingredients!) from scratch.

He didn't grab a loaf of bread from the bakery, slap some supermarket-bought chicken and mayo and lettuce between two slices and call it a day.

He grew the onion and lettuce and tomatoes and cucumber.

He collected honey from bees to make his bread (as growing sugar cane wasn't an option for him in Minnesota).

He milked cows and collected itch weed to make the butter and cheese.

He flew to California to collect ocean water to make the salt.

He slaughtered and plucked a chicken.

Heck, he even made his own press so he could squeeze the oil out of the sunflower seeds he collected in order to make the mayo.

If you're intrigued by what such a six-month-long, $1,500-plus process actually looks like, you can watch the entire saga yourself. (WARNING: ThemTube link!)

OK . . . But why?

So, do you think spending six months and investing over $1,500 to make a sandwich that you could've ordered at your local cafe for $5 is a bit crazy?

If so, that's only because you've been so spoiled by the miracle of human community that you fail to appreciate the incredible benefits that it bestows on your life each and every day. As Andy George explains in the opening video of the series documenting his epic sandwich journey:

The sandwich is a staple of quick and simple meals. But have you ever stopped to wonder what it takes to make all these ingredients? Ever since the advent of agriculture and every technological breakthrough since, the average person has become less and less involved in the creation of their own food supply. It's come to the point now that to feed yourself, all you need to do is peel back the plastic and stick it in the microwave. So that's what I'm setting out to challenge.

George is right, of course. We have indeed been spoiled by the unimaginably vast, decentralized chain of human connection that makes our modern life possible. We are so far removed from the creation of everyday items like a chicken sandwich that not only would we never think of making one from scratch, we wouldn't have the slightest clue how to make it even if we were so inclined.

This is not inherently a bad thing. Do you really need to know the right combination of pigment and paraffin wax required to make an orange crayon so you can help your child color a picture? Do you have to know how to obtain the 6140 Chrome Vanadium steel that is used to make a wrench in order to tighten the nuts on your bicycle? Is it really necessary to know how to make the little plastic cover thingy that goes on the end of your shoelace before you run a marathon? Of course not. Learning how literally everything is made would be an insane and hopeless task.

But to take for granted the unsung miracle of these utterly mundane objects (and the millions more such objects that bless our day-to-day life) is to overlook one of the most profound lessons we can ever learn, namely . . .

Only God Can Make A Sandwich

Perhaps this all sounds familiar to you. Maybe you have that tingling sensation in the back of your mind, as if you've heard something similar before. Perchance this screed on sandwich-making brings wood and graphite writing implements to mind.

If so, then congratulations! You've been listening to The Corbett Report long enough to have heard me ranting about "I, Pencil," the must-read 1958 essay by Leonard E. Read that aims to demonstrate how "[n]o one person—repeat, no one, no matter how smart or how many degrees follow his name—could create from scratch a small, everyday pencil, let alone a car or an airplane."

If, for some reason, you haven't read Read's essay yet, what are you doing? Drop everything and read it. Read it now!

Go on. I'll wait. . . .

. . . OK, now that you've read the essay, you understand three important things.

Firstly, you understand that the humble little pencil is indeed a much more complicated and intricate item than you gave it credit for, with materials (cedar, graphite, candelilla wax, castor oil, zinc, copper, pumice, etc.) from far-flung corners of the globe (Oregon, Mississippi, Mexico, Sri Lanka, Indonesia, Italy, etc.) being processed in myriad ways (cut, kiln-dried, tinted, glued, treated, lacquered, vulcanized, etc.) before being assembled into the writing implement we all know and love.

Secondly, you understand that not one of the millions of people who ultimately take part in this elaborate, globe-spanning operation—the loggers and miners and millworkers and truck drivers and factory workers involved in collecting and assembling the pencil's components, let alone the people involved in keeping those workers fed and clothed and housed—themselves know how to find, source, collect, treat and assemble the raw constituents of the pencil into an actual pencil. In fact, none of them are engaged in their individual tasks for the express purpose of obtaining a pencil. And yet, there the pencil sits, a silent testament to the miracle of human cooperation.

Thirdly, you know that no one could coordinate such an endeavour, oversee every step of the process and direct each person in their contribution to the pencil's creation. In fact, given the diffuse chain of human relationships needed to make this entire worldwide operation work—the "miners and those who make their many tools and the makers of the paper sacks in which the graphite is shipped and those who make the string that ties the sacks and those who put them aboard ships and those who make the ships," let alone the lighthouse keepers and hemp growers and tool makers and chefs and the "untold thousands of persons [who] had a hand in every cup of coffee the loggers drink" that Read's eponymous pencil tells us about—no one could even possibly itemize all of the various professions, products and materials that are required to make such a simple thing as a pencil.

Or a sandwich. Who made the airplane George used to fly to California to collect the ocean water for the salt for his sandwich? Or the boat he used to go collect the water? Or the fuel that was used to power the boat? Who made the food he ate while he was on his six-month sandwich quest? Who fed those people? Who made their clothes? etc., etc., etc. . . .

And yet there are those who not only presume to be able to coordinate the creation of something as seemingly simple as a pencil or a sandwich, but people who think they could direct entire societies, control the activities of millions or even billions of human beings to ensure that their interactions all work harmoniously toward some goal chosen by this handful of would-be central planners. The hubris of such a claim is mind-boggling, but it is taken for granted by statists of all sorts whenever they vote for candidates who promise to accomplish just such an impossible task.

As Leonard Read's son, Lawrence Read, points out in his introduction to his father's essay, this hubris is not just shared by the tyrants of the past—people like Maximilien Robespierre, the man who was responsible for the Reign of Terror in the wake of the French Revolution and who is credited with coining the expression "On ne saurait pas faire une omelette sans casser des oeufs" (You can't make an omelette without breaking some eggs)—but also by ordinary people, whose unthinking acceptance of the doctrines of the social engineers is one of the greatest impediments to human liberty.

Robespierre and his guillotine broke eggs by the thousands in a vain effort to impose a utopian society with government planners at the top and everybody else at the bottom. That French experience is but one example in a disturbingly familiar pattern. Call them what you will—socialists, interventionists, collectivists, statists—history is littered with their presumptuous plans for rearranging society to fit their vision of the common good, plans that always fail as they kill or impoverish other people in the process. If socialism ever earns a final epitaph, it will be this: Here lies a contrivance engineered by know-it-alls who broke eggs with abandon but never, ever created an omelet.

None of the Robespierres of the world knew how to make a pencil, yet they wanted to remake entire societies. How utterly preposterous, and mournfully tragic! But we will miss a large implication of Leonard Read’s message if we assume it aims only at the tyrants whose names we all know. The lesson of “I, Pencil” is not that error begins when the planners plan big. It begins the moment one tosses humility aside, assumes he knows the unknowable, and employs the force of the State against peaceful individuals. That’s not just a national disease. It can be very local indeed.

In our midst are people who think that if only they had government power on their side, they could pick tomorrow’s winners and losers in the marketplace, set prices or rents where they ought to be, decide which forms of energy should power our homes and cars, and choose which industries should survive and which should die. They should stop for a few moments and learn a little humility from a lowly writing implement.

So, where does this leave us? It leaves us in the position of being humbled by the lowliest item of them all: a pencil. Or a chicken sandwich.

And, as Leonard Read reminds us at the end of his essay, until we learn the lesson of the true nature of this seemingly simple object, we will never attain freedom.

It has been said that “only God can make a tree.” Why do we agree with this? Isn’t it because we realize that we ourselves could not make one? Indeed, can we even describe a tree? We cannot, except in superficial terms. We can say, for instance, that a certain molecular configuration manifests itself as a tree. But what mind is there among men that could even record, let alone direct, the constant changes in molecules that transpire in the life span of a tree? Such a feat is utterly unthinkable!

I, Pencil, am a complex combination of miracles: a tree, zinc, copper, graphite, and so on. But to these miracles which manifest themselves in Nature an even more extraordinary miracle has been added: the configuration of creative human energies—millions of tiny know-hows configurating naturally and spontaneously in response to human necessity and desire and in the absence of any human masterminding! Since only God can make a tree, I insist that only God could make me. Man can no more direct these millions of know-hows to bring me into being than he can put molecules together to create a tree.

The above is what I meant when writing, “If you can become aware of the miraculousness which I symbolize, you can help save the freedom mankind is so unhappily losing.” For, if one is aware that these know-hows will naturally, yes, automatically, arrange themselves into creative and productive patterns in response to human necessity and demand— that is, in the absence of governmental or any other coercive master-minding—then one will possess an absolutely essential ingredient for freedom: a faith in free people. Freedom is impossible without this faith.

Well said.

But I know you're all on the edge of your seat, eager to learn the answer to the one true, burning question arising from today's exploration: How did George's $1,500, six-month chicken sandwich actually taste?

Six months of his life and $1,500 for a "not bad" sandwich that he could've bought at the local diner for a fiver.

Well, at least he managed to parlay a career out of that sandwich.

And me? Full disclosure: at least one sandwich was consumed in the writing of this essay. Needless to say, I didn't make it from scratch.

Like this type of essay? Then you’ll love The Corbett Report Subscriber newsletter, which contains my weekly editorial as well as recommended reading, viewing and listening. If you’re a Corbett Report member, you can sign in to corbettreport.com and read the newsletter today.

Not a member yet? Sign up today to access the newsletter and support this work.