by James Corbett

corbettreport.com

July 9, 2023

Have you heard the latest?

Canadians are losing their access to online news thanks to a new bill that would make tech companies liable for so much as linking to news stories.

French President Macron is mulling a social media shutdown in the name of quelling France's social unrest.

Meta's new "Twitter killer" Threads app is (surprise, surprise!) censoring from day one.

And the UK government is considering a proposal to give their NSA equivalent, the GCHQ, unprecedented, sweeping new powers to monitor internet logs in real-time.

Are you noticing a pattern?

Yes, the Internet—the "Information Superhighway" version of the "Internet" that was sold as a digital panacea to a credulous public in the 1990s, that is—is now officially dead.

So what does this mean? And where do we go from here? Today, I'll get to the bottom of the dead internet theory and what conspiracy realists should make of this news.

The Internet Theory

If you lived through the '90s, congratulations! You had a front row seat to a fundamental transformation of society the likes of which hasn't been seen by any generation since the days of Gutenberg.

Unless you were working at a university or a US government lab, you started the decade utterly ignorant of email and message boards and even the basic rudiments of computer networking. But by the time you were ringing in the millennium, you were (more likely than not) online, sending emails and surfing the web and getting into your first online flame wars.

You lived through the endless talk about the Information Superhighway. You survived the interminable propaganda designed to convince you that the Internet (capital "I" and all, as if cyberspace was some newly discovered foreign country that we were about to colonize) was going to democratize information, give everyone a voice in the conversation in the digital town square and unite us all in peace, harmony and understanding. And you endured ceaseless segments of befuddled TV hosts informing their audiences about URLs and email addresses as if they were reading an encyclopedia entry in a foreign language, carefully intoning every letter, colon and backslash and tittering over how to pronounce the "@" symbol.

It was all a lie, of course. Unbeknownst to the general public at the time, the internet did not spring fully formed from the heads of the Silicon Valley nerds in the 1990s. In fact, its origins go back much further. As we eventually came to learn, the internet actually began life as the ARPANET, a US Department of Defense project whose goal, according to the former director of DARPA, "was to exploit new computer technologies to meet the needs of military command and control against nuclear threats, achieve survivable control of US nuclear forces, and improve military tactical and management decision making."

As it turns out, even this "nuclear resistant network" story is a limited hangout. As students of my Mass Media: A History online course will know by now, the ARPANET wasn't just about securing America's nuclear war-fighting capabilities but also about improving Uncle Sam's tools of surveillance and control for counterinsurgency operations. This thread of the story—involving characters like psychologist-turned-computer scientist J.C.R. Licklider and his quest to build a tool capable of collecting, storing and analyzing mind-boggling amounts of information on every entity and individual deemed an enemy of the US government—has been largely lost to time.

As Yasha Levine documents in his book on Surveillance Valley, however, anti-Vietnam War protesters on US campuses in the 1960s recognized the ARPANET and The Cambridge Project and associated computer networking research projects for what they were: attempts to find a way to quash dissent against the powers-that-shouldn't-be wherever and whenever that dissent arose.

One 1969 pamphlet on the growing peril of military-funded computer databases noted:

Clearly the ARPA network has practical military implications. While not a weapon of destruction per se, it will contribute a necessary link to a powerful automated military control system.

And another 1960s pamphlet on the looming threat of silicon surveillance observed:

The whole computer set-up and the ARPA computer network will enable the government, for the first time, to consult relevant survey data rapidly enough to be used in policy decisions. The net result of this will be to make Washington's international policeman more effective in suppressing popular movements around the world.

Unsurprisingly, perhaps, public awareness of the perils of digital dictatorship and the mechanized menace of the "Octoputer" (with its technological tracking tendrils snaking their way into every nook and cranny of your life) got lost along the way. By the '90s, people were ready to believe that the digitization of social relations was a boon to humanity and that the world would be better off for it.

Meanwhile, here in the 2020s, the gloss of the (capital "I") Internet fairy tale has long since worn off. And, now that we have long since passed the point of no return on this roller coaster ride into the digital abyss, we are finding that the dream sold to the public three decades ago—the hopium-induced phantasm of Information Superhighways and technological liberation—is now officially dead.

The Dead Internet Theory

Have you heard of the "dead internet theory"?

In a nutshell, it posits that the Internet of old—the wild and wacky, old-school, capital "I" Internet of human-generated fun and weirdness—died in 2016. Since then, according to adherents of this premise, the majority of everything we encounter online has been bot-generated.

If this theory is correct, then the computer-created content of the dead internet includes not just the obviously inhuman content on the web—the spam that overruns every unmoderated comment section, for instance, or the botnets that flood social media with identically worded propaganda posts—but everything: the content itself, the commentary on that content, the "people" we interact with online, even audio podcasts and video vlogs and other seemingly human-generated media.

Whatever one makes of this dead internet theory, it is certainly neither the first nor the last time that the internet has been declared dead.

In 1998, Paul Krugman infamously declared the internet to be a hype-driven fad, boldly predicting it would have no more impact on the economy than the fax machine.

In 2000, Bob O'Keefe, a professor of information management at Brunel University, opined that the "internet is dead" because "young people want mobility and social interaction, not computers."

In 2002, CNET announced the death of the free web (free as in free beer, that is, not free as in free speech).

In 2007, Mark Cuban told us that "the internet’s dead" and that "it's over" before contradictorily asserting that "the internet’s for old people" because it had become stagnant.

In 2010, Wired confirmed that the web was indeed dead (having been replaced by apps).

In 2015, Vox also pronounced the internet officially dead, a point contested by their MSM brethren over at The New York Times, who asserted in 2017 that the internet was merely in the process of dying.

Even the CBC has gotten in on the act (years after everyone else, of course), daring to ask in 2020 if "the dream of an 'open' internet" is in fact dead.

Some astute observer may have even written "April 10, 2021" on the internet's death certificate in commemoration of the main Corbett Report channel being scrubbed from ThemTube that day. (I mean, I haven't seen anyone actually do that, but I'm sure someone could!)

Whichever death certificate you choose to believe, though, it's hardly worth quibbling over the exact date and time of the internet's death at this point.

Anyone who has been paying attention to the rise of the censorship-industrial complex over the past decade, anyone who has seen country after country after country after country after country implementing internet shutdowns and great firewalls and internet kill switches to keep their tax cattle from accessing online information detrimental to the powers-that-shouldn't-be, anyone who has seen the push for age verification and digital identification and "driver's licenses" for the internet knows the truth by now: to whatever extent the "Internet" of yore ever existed, it is now well and truly gone.

Heck, I just spent ten minutes searching various search engines with multiple queries to find an article whose exact headline I already knew. (And, irony of ironies, that article is about Canada's new online censorship bill).

My friends, it is now beyond doubt that we are no longer living in the utopian era of the Information Superhighway but in the dystopian nightmare of the digital gulag.

The Internet is dead.

Long Live the Internet?

But what does it mean that the free and open Internet is dead? After all, the ARPANET was designed to be able to survive and to continue functioning even in the wake of nuclear Armageddon, wasn't it? So how can some meddling governments take the whole thing down?

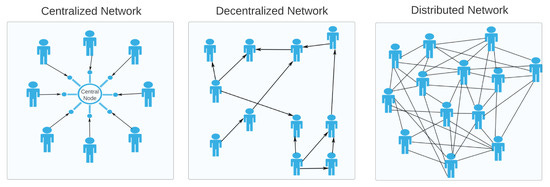

The most obvious answer is that the clueless masses who began logging on to the internet over the past two decades had no clue about the benefits of decentralization and merely gravitated to the most convenient and popular online spaces. By eschewing the labour of creating their own websites (or even designing their own geocities blog or Myspace page), by forsaking the quest to find new, unexplored corners of the net, they unwittingly recreated the dinosaur media paradigm in the new digital domain.

The parallels are striking: just as there were a handful of TV networks and newspapers and media companies that were able to dictate what almost everyone saw, heard, talked about and thought about on a daily basis in the old dinosaur media paradigm, there are now a handful of social media platforms where people are allowed to create a standardized, cookie-cutter profile and talk about the (fact-checker approved) news of the day.

And, just like that, the wacky, weird, intensely personal web of blogs and fora and message boards became the handful of standardized, soulless, corporate social media sites that dominate the web today.

There's even more to the story, though. The truth is that the Internet of yesteryear became the internet of today through a series of actions designed to make a decentralized, distributed network of information exchange into a centralized network of information control.

In fact, from its earliest beginnings, the ARPANET relied on a single "HOSTS.TXT" file maintained by the Stanford Research Institute to map hostnames to IP addresses. That system eventually developed into the Domain Name System that exists today, turning the inscrutable 77.235.50.111 IP address into the human-readable corbettreport.com.

Of course, most people don't give a moment's thought to the domain name system—how it is managed, who controls it, or why such a centralized directory is needed at all to run a supposedly decentralized network—until their domain is seized by the feds, that is.

Nor do they consider the dangers of relying on one of the few big-name web hosts or content delivery networks to host their web site . . . until their hosting is pulled and no one can access their site anymore.

Nor do they ponder the implications for the free, open, decentralized web if everyone relies on a handful of social media platforms run by a handful of Big Tech companies to provide access to their online "friends" . . . until their profile is suspended or their account removed for wrongthink.

Of course, as viewers of #SolutionsWatch know, the concept of truly decentralized communication is still alive and well. From Bastyon to Qortal to nostr to Blockchain DNS and many other projects besides, there is no shortage of developers who are working on ways for people to use the internet as it was intended: as a decentralized, distributed network with no middleman capable of stepping into your peer-to-peer information exchange.

Of course, the majority of people don't care about decentralized communication. They're happy to watch videos on YouTube and to share news on Twitter and to post vacation photos to Instagram and to pretend to be Facebook friends with people they haven't seen since grade school and to call all of this "the internet." They don't care about censorship or government surveillance. After all, if something is banned from this or that social media platform, then it's probably Thoughtcrime and deserves to be censored anyway, right?

But beyond the censorship, there's an even sadder story underlying the tale of the death of the internet. It involves the death of the human element of the early world wide web, a tragedy that the Dead Internet Theory is gesturing toward in a ham-handedly literal fashion.

Although it's incomprehensible for people growing up in today's depressing, enraging, clickbaity internet environment, the truth is that 30 years ago the world wide web was a fun, zany, lively space for encountering truly unique and idiosyncratic sites of all sorts.

The excitement of finding that group of people who cared as much as you did about stamp collecting or Scandinavian doom metal or 19th century crockery or whatever ridiculously niche topic you happened to be interested in is perhaps indescribable to those habituated to mindlessly scrolling through algorithmically provided feeds of increasingly bot-generated content on the handful of boring corporate social media platforms we're confined to today.

Oh, and those twirling "under construction" graphics and flashing, seizure-inducing backgrounds of poorly designed 1990s websites? Humorous as they appear to us in retrospect, they spoke to the human nature of the world wide web back then.

Contrast the off-the-wall individuality of an early 1990s website with the impersonal, inhuman, barren landscape of Facebook or reddit, and you can't help but be left with the feeling that we are slowly being turned into machines ourselves, devoid of personality or individual creativity.

Perhaps, then, it isn't a bad thing that the decentralized networks and platforms that are coming online right now are not popular. They are not being brought down to the lowest common denominator by the Joe Sixpacks and Jane Soccermoms of the world. Perhaps it's through these new, exciting, experimental technologies that we can finally shed the carapace of the dead internet and rediscover that place of human connection that seemed to be at our fingertips lo those many decades ago.

The early internet was pioneered by the misfits, the geeks, the pioneers, the weirdos of all stripes who were willing to go out of their way to create something novel and different. The new internet will be pioneered by them, too. Hope to see you there.